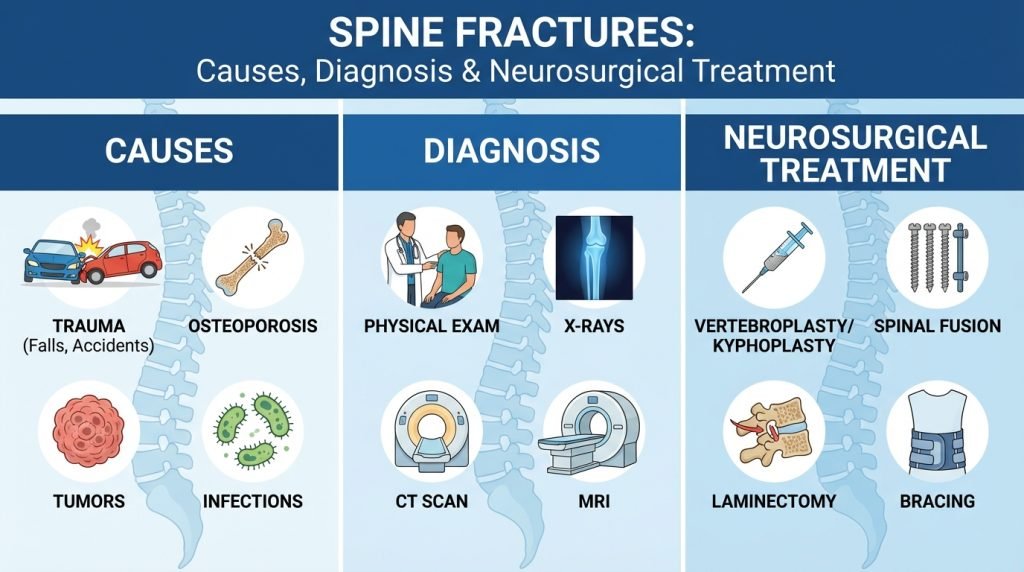

Spine Fractures: Causes, Diagnosis & Neurosurgical Treatment

A spine fracture—also known as a vertebral fracture—is a serious injury that involves a break in one or more of the bones (vertebrae) that make up the spinal column. Unlike a broken arm or leg, a fracture in the spine carries the potential risk of damaging the spinal cord or surrounding nerve roots, which can lead to permanent changes in strength, sensation, and bodily functions.

Whether caused by a sudden high-impact accident or the slow thinning of bones due to osteoporosis, understanding the mechanics of a spinal fracture is the first step toward effective recovery. This guide explores the types of fractures, how they are diagnosed, and the advanced neurosurgical options available to restore stability.

1. Common Causes of Spine Fractures

The cause of a spinal fracture often determines the type of fracture sustained and the urgency of treatment.

Trauma and High-Impact Accidents

In younger populations, the majority of spine fractures result from high-energy trauma. These include:

- Motor Vehicle Accidents (MVAs): The sudden force of impact can crush or snap the vertebrae.

- Falls from Heights: Common in construction or extreme sports.

- Sports Injuries: High-contact sports or diving into shallow water.

Osteoporosis and Bone Density Issues

In older adults, osteoporosis is the leading cause of spine fractures. As bones become porous and brittle, even a minor movement—such as sneezing, reaching for a shelf, or a small trip—can cause a Vertebral Compression Fracture (VCF).

Pathological Fractures (Tumors)

Certain types of cancer, particularly those that metastasize (spread) to the bone, can weaken the vertebrae to the point of collapse. This is known as a pathological fracture and often requires a combined approach of oncology and neurosurgery.

2. Types of Spinal Fractures

Neurosurgeons classify spine fractures based on the pattern of injury and whether the spine remains “stable.”

- Compression Fracture: Common in osteoporosis, the front of the vertebra collapses while the back remains stable.

- Burst Fracture: The vertebra is crushed in all directions, often sending bone fragments into the spinal canal. These are highly dangerous and often require immediate surgery.

- Flexion-Distraction (Chance) Fracture: Often seen in car accidents where the upper body is thrown forward while the pelvis is secured by a lap belt, literally pulling the spine apart.

- Fracture-Dislocation: This occurs when the bone breaks and the ligaments tear, causing the vertebrae to slide off one another. This is the most unstable type of injury and carries the highest risk of paralysis.

3. Symptoms and “Red Flags”

The symptoms of a spine fracture can range from a dull ache to complete loss of function.

Physical Symptoms

- Sudden, severe back pain: This is the most common indicator, often worsening with movement.

- Deformity: A “hunchback” appearance (kyphosis) can develop after multiple compression fractures.

- Loss of height: Over time, as vertebrae collapse, the patient may physically shrink.

Neurological “Red Flags”

If the fracture compresses the spinal cord, immediate neurosurgical intervention is required. Signs include:

- Numbness or tingling in the arms or legs.

- Weakness or inability to move limbs.

- Loss of bowel or bladder control (a sign of Cauda Equina Syndrome).

- Difficulty walking or maintaining balance.

4. How are Spine Fractures Diagnosed?

A rapid and accurate diagnosis is critical to preventing permanent nerve damage.

- Physical and Neurological Exam: The doctor tests for “point tenderness” over the spine, checks reflexes, and assesses muscle strength.

- X-Ray: The first line of defense to see the general alignment of the bones.

- CT Scan: Provides a detailed, 3D cross-section of the bone structure, helping the surgeon see if bone fragments have entered the spinal canal.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Critical for assessing the “soft tissues,” such as the spinal cord, nerves, and ligaments. It also helps determine if a fracture is “acute” (new) or “chronic” (old).

- DEXA Scan: If osteoporosis is suspected, a bone density scan is performed to assess future fracture risk.

5. Neurosurgical Treatment Options

The goal of treatment is to stabilize the spine, alleviate pain, and protect the spinal cord.

Non-Surgical Management (Conservative Care)

For stable fractures (like minor compression fractures), non-surgical routes are preferred:

- Bracing: A rigid back brace (TLSO) limits motion and allows the bone to knit back together naturally.

- Pain Management: Medications to manage inflammation and nerve pain.

- Physical Therapy: Started once the bone begins to heal to strengthen the supporting core muscles.

Minimally Invasive Procedures

For fractures that do not involve the spinal cord but cause severe pain, two procedures are common:

- Vertebroplasty: Bone cement is injected into the fractured vertebra to stabilize it.

- Kyphoplasty: A small balloon is inflated inside the collapsed bone to restore its height before the cement is injected. This is highly effective for osteoporotic compression fractures.

Major Surgical Interventions

For unstable fractures or those causing neurological deficits, “open” surgery is required:

- Spinal Decompression (Laminectomy): The surgeon removes the back part of the vertebra (lamina) or bone fragments to “decompress” the spinal cord and give it room to heal.

- Spinal Fusion: Metal rods, screws, and bone grafts are used to permanently join two or more vertebrae together, creating a solid “bridge” that prevents painful or dangerous movement.

6. Recovery and Long-Term Outlook

Recovery from a spine fracture is a multi-month journey.

- Hospital Stay: Patients who undergo fusion may stay for 3–5 days. Those having kyphoplasty often go home the same day.

- The “Six-Month Mark”: Most bone healing occurs within 3 to 6 months. During this time, patients must avoid bending, lifting, or twisting (the “BLT” rule).

- Bone Health: If the fracture was due to osteoporosis, long-term treatment with calcium, Vitamin D, and bone-strengthening medications (bisphosphonates) is essential to prevent a “domino effect” of future fractures.