Hydrocephalus: Causes, Symptoms & Neurosurgical Solutions

Often referred to by the outdated term “water on the brain,” hydrocephalus is a complex neurological condition characterized by an abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the ventricles (cavities) of the brain. This build up creates harmful pressure on the brain’s delicate tissues, potentially leading to permanent damage if left untreated.

In the modern era of neurosurgery, hydrocephalus is no longer the life-limiting diagnosis it once was. With advanced shunting technologies and minimally invasive endoscopic procedures, patients can lead full, active lives. This guide explores the mechanics of hydrocephalus, its age-specific symptoms, and the cutting-edge surgical solutions used today.

1. What is Hydrocephalus? The Science of CSF

To understand hydrocephalus, one must understand Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF). CSF is a clear, colourless liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. It serves three vital purposes:

- Cushioning: Acting as a shock absorber for the brain.

- Nutrient Delivery: Carrying essential nutrients to the brain and removing waste.

- Pressure Regulation: Maintaining a stable environment inside the skull.

In a healthy brain, CSF is constantly produced, circulated through the ventricles, and then absorbed into the bloodstream. Hydrocephalus occurs when this balance is disrupted, either because the fluid is blocked (obstructive) or because the body cannot absorb it properly (communicating).

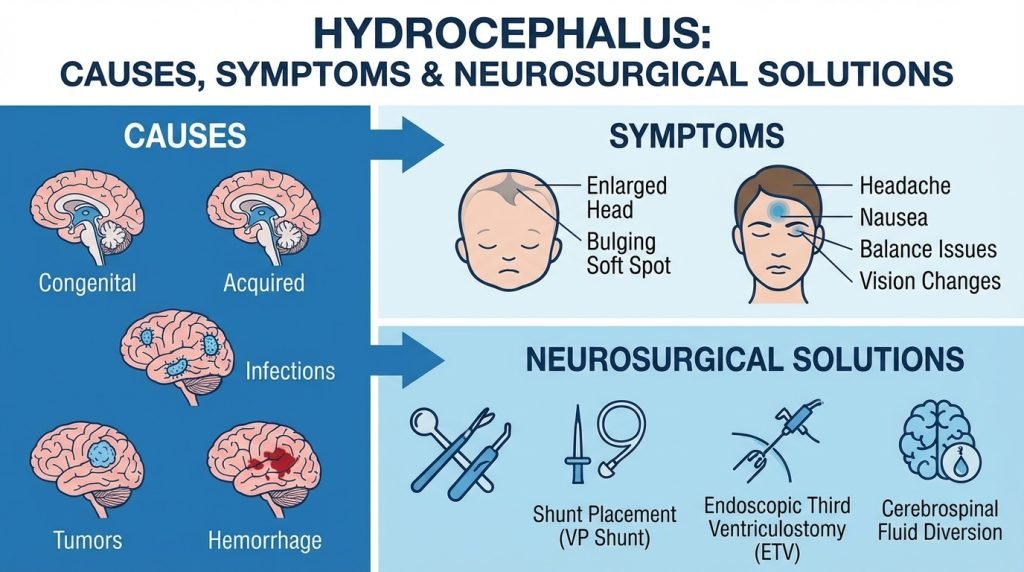

2. Common Causes of Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus can be present at birth or acquired later in life. It is generally categorized into three types based on the cause:

Congenital Hydrocephalus

Present at birth, this is often caused by a complex interaction of genetic and environmental factors during fetal development. Common causes include:

- Aqueductal Stenosis: A narrowing of the small passage between the third and fourth ventricles.

- Spina Bifida: A neural tube defect where the spine doesn’t close properly.

- Brain Malformations: Such as Dandy-Walker Syndrome or Chiari Malformation.

Acquired Hydrocephalus

This develops after birth and can affect individuals of any age. Triggers include:

- Head Trauma: Brain injuries can cause bleeding or inflammation that blocks CSF flow.

- Brain Tumors: A growth can physically obstruct the ventricles.

- Meningitis: Infections can scar the membranes that absorb CSF.

- Intraventricular Hemorrhage: Common in premature infants when blood vessels in the brain rupture.

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH)

NPH primarily affects older adults (usually 60+). While the pressure in the brain may appear normal during a spinal tap, the ventricles enlarge, causing a specific triad of symptoms. NPH is often misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease.

3. Recognizing the Symptoms: Age Matters

The symptoms of hydrocephalus vary significantly depending on the age of the patient and how quickly the pressure is rising.

In Infants (0–2 years)

- Unusual Head Growth: A rapid increase in head circumference.

- Bulging Fontanelle: The “soft spot” on the top of the head feels tense or bulging.

- “Sunsetting” Eyes: The eyes appear to gaze downward constantly, showing the white of the eye above the iris.

- Extreme Irritability and Projectile Vomiting.

In Children and Adolescents

- Severe Headaches: Often accompanied by nausea and vomiting, especially in the morning.

- Blurred or Double Vision: Caused by pressure on the optic nerves.

- Cognitive Delays: Difficulty focusing in school or a sudden drop in academic performance.

- Loss of Coordination: Frequent tripping or difficulty with fine motor skills.

In Older Adults (Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus)

NPH is characterized by the “Adams Triad,” often remembered by the mnemonic “Wet, Wobbly, and Wacky”:

- Wet (Urinary Incontinence): A sudden, frequent urge to urinate or loss of bladder control.

- Wobbly (Gait Instability): A characteristic “magnetic gait” where the person feels like their feet are stuck to the floor.

- Wacky (Cognitive Decline): Mild dementia, forgetfulness, or loss of interest in daily activities.

4. Diagnostic Procedures

If hydrocephalus is suspected, a neurologist or neurosurgeon will use several tools to confirm the diagnosis:

- Brain Imaging (MRI or CT): These scans provide a clear picture of the ventricles to see if they are enlarged.

- Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap): Used primarily in NPH cases to see if removing a small amount of CSF temporarily improves the patient’s walking or thinking.

- Intracranial Pressure (ICP) Monitoring: A small sensor is placed inside the skull to measure pressure levels over 24–48 hours.

5. Neurosurgical Solutions: Shunts and ETV

There are no effective medications to treat hydrocephalus; surgery is the only definitive solution.

The VP Shunt (Venticuloperitoneal Shunt)

The most common treatment involves the surgical placement of a shunt system.

- How it works: A flexible tube is placed in the brain’s ventricle. The tube runs under the skin to another part of the body (usually the abdomen), where the excess CSF can be absorbed into the bloodstream.

- The Valve: A pressure-controlled valve ensures that only the right amount of fluid is drained. Some modern valves are “programmable,” allowing the surgeon to adjust the drainage rate from outside the skin using a magnet.

ETV (Endoscopic Third Ventriculostomy)

For patients with “obstructive” hydrocephalus, ETV is a minimally invasive alternative that avoids the need for a permanent shunt.

- How it works: A neurosurgeon uses a tiny camera (endoscope) to enter the ventricles and create a small hole in the floor of the third ventricle. This allows the CSF to bypass the blockage and flow to its natural absorption site.

- Benefits: No foreign hardware in the body and a lower long-term risk of infection.

6. Recovery, Long-Term Care, and Risks

While surgery is highly effective, hydrocephalus is a lifelong condition that requires vigilant monitoring.

Post-Surgical Recovery

Most patients spend 2 to 4 days in the hospital. Children often recover quickly, while older adults with NPH may need several weeks of physical therapy to regain their balance.

Potential Complications

- Shunt Malfunction: The tube can become blocked, disconnected, or the valve can fail.

- Infection: This is most common in the first few months after surgery and requires immediate medical attention.

- Over-drainage: If too much fluid is removed, it can cause the brain to pull away from the skull, leading to headaches or hematomas.

Living with Hydrocephalus

Patients with shunts can lead normal lives, including playing sports (usually with head protection) and traveling. However, they must be aware of the “Red Flags” of shunt failure, such as sudden headaches, lethargy, or a return of original symptoms.