Epilepsy Surgery: Who Is a Candidate & What to Expect

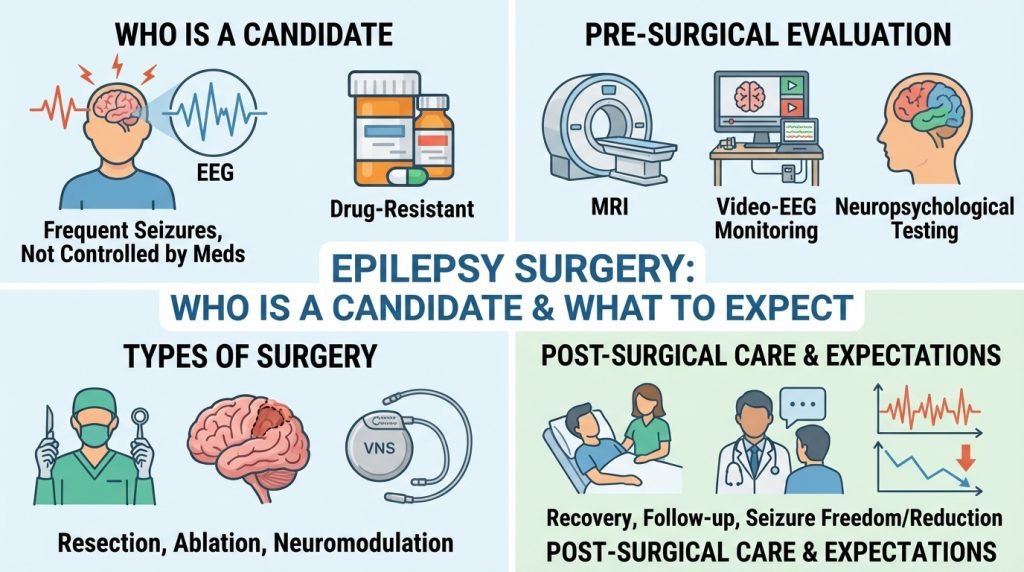

For millions of people worldwide, epilepsy is managed effectively through anti-seizure medications (ASMs). However, for approximately 30% of patients, medications fail to provide adequate seizure control. This condition is known as drug-resistant or refractory epilepsy.

When medications fail, epilepsy surgery often transitions from a “last resort” to the most effective path toward a seizure-free life. Modern neurosurgical techniques have made these procedures safer and more precise than ever before. This guide explores the criteria for candidacy, the various types of surgical interventions, and the comprehensive journey toward recovery.

1. Who Is a Candidate for Epilepsy Surgery?

Not everyone with epilepsy is a candidate for surgery. The selection process is rigorous to ensure that the procedure will be both safe and effective.

Defining Drug-Resistant Epilepsy

A patient is generally considered a candidate for a surgical evaluation if they have failed to achieve seizure freedom after trying two tolerated and appropriately chosen anti-seizure medications. Statistics show that if the first two medications fail, the likelihood of a third medication working is less than 5%.

Focal vs. Generalized Seizures

Surgery is most successful when seizures are focal, meaning they originate in one specific, identifiable area of the brain (the “seizure focus”). if the seizures are generalized (involving the whole brain from the start), traditional resective surgery may not be an option, though neuromodulation might be considered.

Functional Mapping

A critical factor in candidacy is whether the seizure focus is located in an “eloquent” area of the brain—parts responsible for vital functions like speech, movement, vision, or memory. If the focus is in an area that cannot be safely removed, alternative “disconnective” or “palliative” procedures are explored.

2. The Pre-Surgical Evaluation: The Roadmap to Success

Before a surgeon ever picks up a scalpel, a multidisciplinary team (neurologists, neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists) performs a “Phase I” and sometimes a “Phase II” evaluation.

Phase I: Non-Invasive Testing

- Video-EEG Monitoring: You stay in an Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (EMU) for several days while being recorded on video and EEG to “capture” your seizures.

- High-Resolution MRI (3-Tesla): To look for structural abnormalities like scars, tumors, or cortical dysplasia.

- PET and SPECT Scans: These imaging tests look at brain metabolism and blood flow to see where seizures start.

- Neuropsychological Testing: To assess how epilepsy has affected your memory, language, and cognitive function.

Phase II: Invasive Monitoring

If non-invasive tests don’t clearly identify the seizure focus, surgeons may use Stereo-EEG (SEEG). This involves placing tiny electrodes deep into the brain through “keyhole” incisions to map seizure activity with pinpoint accuracy.

3. Types of Epilepsy Surgery

Depending on the results of the evaluation, one of the following procedures may be recommended:

A. Resective Surgery (The Gold Standard)

The most common type of surgery, where the surgeon removes the specific area of the brain where seizures originate.

- Temporal Lobe Resection: The most frequent and successful type, often resulting in seizure freedom for 60-80% of patients.

- Lesionectomy: Removal of a specific lesion (tumor or vascular malformation) causing the seizures.

B. Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy (LITT)

A minimally invasive alternative to open surgery. A tiny laser fiber is inserted into the seizure focus, and heat is used to destroy the abnormal tissue. This results in faster recovery times and less scarring.

C. Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) & Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS)

For patients whose seizure focus cannot be removed, “brain pacemakers” are used.

- RNS: A device monitors brain waves 24/7 and delivers a small electrical pulse to stop a seizure before it starts.

- DBS: Delivers continuous electrical signals to specific brain circuits to reduce seizure frequency.

D. Hemispherectomy & Corpus Callosotomy

Typically reserved for severe pediatric cases. These involve disconnecting the two halves of the brain or removing one hemisphere to prevent the spread of catastrophic seizures.

4. What to Expect During the Procedure

The Surgery

Most resective surgeries take between 3 and 6 hours. For certain procedures near speech centers, a “functional mapping” or awake brain surgery may be performed to ensure the surgeon does not damage critical areas.

Immediate Post-Op

You will wake up in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for close monitoring. Most patients experience:

- A moderate headache.

- Nausea (controlled with medication).

- Swelling around the eyes or scalp.

5. The Recovery Process and Life After Surgery

Recovery is a marathon, not a sprint. While the physical incisions heal quickly, the brain needs time to adjust.

Hospital Stay

Most patients spend 2 to 5 days in the hospital. Minimally invasive laser surgery patients may even go home the next day.

The First Six Weeks

- Rest: Fatigue is common as the brain heals.

- Activity: Avoid heavy lifting and strenuous exercise. Walking is encouraged.

- Medication: You must continue taking your seizure medications after surgery. The brain needs a “seizure-free interval” before doctors consider tapering down medications, which usually happens 6–24 months post-op.

Success Rates

Success is measured on the Engel Scale:

- Class I: Seizure-free (the ultimate goal).

- Class II: Rare disabling seizures.

- Class III: Worthwhile improvement.

6. Risks and Considerations

All surgeries carry risks, including infection, bleeding, or reactions to anesthesia. Specific risks for epilepsy surgery include:

- Memory or Language Changes: Especially with temporal lobe surgery.

- Visual Field Deficits: Depending on the location of the resection.

- Mood Changes: Some patients experience temporary depression or anxiety during the adjustment period.