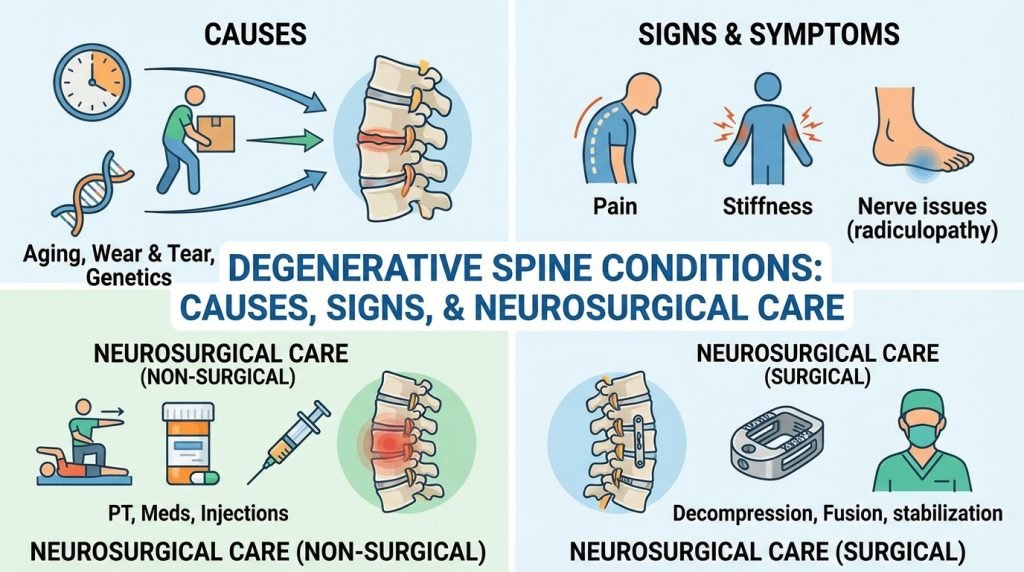

Degenerative Spine Conditions: Causes, Signs, and Neurosurgical Care

The human spine is a complex architectural marvel, designed to provide structural support, protect the spinal cord, and enable a vast range of motion. However, as a weight-bearing structure, it is subject to constant mechanical stress. Over time, this “wear and tear” leads to degenerative spine conditions, a spectrum of disorders that affect millions of adults worldwide.

While back pain is often dismissed as a standard part of aging, degenerative changes can lead to debilitating pain, nerve damage, and loss of mobility. Understanding the causes, recognizing the early signs, and knowing the latest in neurosurgical care are essential steps in reclaiming your quality of life.

What are Degenerative Spine Conditions?

Degenerative spine disease is not a single diagnosis but rather an umbrella term describing the gradual loss of normal structure and function of the spine. These changes typically occur in the intervertebral discs, facet joints, and spinal ligaments.

As we age, the discs that act as shock absorbers between the vertebrae lose their water content and elasticity. This process, known as desiccation, reduces the disc’s ability to handle pressure, leading to a cascade of issues including bone spurs, thickened ligaments, and compressed nerves.

Common Degenerative Conditions

- Degenerative Disc Disease (DDD): Despite the name, this is a condition where the discs between vertebrae break down, often leading to chronic lower back or neck pain.

- Spinal Stenosis: A narrowing of the spaces within your spine, which can put pressure on the nerves that travel through the spine.

- Spondylolisthesis: Occurs when one vertebra slips forward over the one below it, often due to facet joint degeneration.

- Herniated Discs: Also known as a “slipped” or “ruptured” disc, where the inner soft material of the disc leaks through a tear in the tougher exterior.

- Osteoarthritis of the Spine: The breakdown of the cartilage of the joints and discs in the neck and lower back.

Causes and Risk Factors

While aging is the primary driver of spinal degeneration, it is rarely the only factor. Several elements contribute to the speed and severity of the breakdown.

- Genetics: Family history plays a significant role in how early and how severely your spine will degenerate.

- Repetitive Stress: Careers involving heavy lifting, frequent twisting, or prolonged sitting can accelerate the wear on spinal joints.

- Obesity: Excess body weight puts constant mechanical stress on the lumbar spine (lower back), speeding up disc compression.

- Smoking: Tobacco use restricts blood flow to the spinal discs, preventing them from receiving the nutrients needed for self-repair.

- Acute Injury: Previous trauma, such as a sports injury or a car accident, can create structural instabilities that lead to premature degeneration.

Recognizing the Signs: When to Seek Help

Degenerative spine conditions can manifest in a variety of ways, ranging from a dull, persistent ache to sharp, radiating electrical shocks.

1. Radiculopathy (Nerve Root Compression)

When a degenerated structure (like a bone spur or herniated disc) presses on a nerve root, it causes pain that “radiates” to other parts of the body.

- Sciatica: Sharp pain that travels from the lower back down through the buttocks and into the legs.

- Cervical Radiculopathy: Pain, numbness, or tingling that radiates from the neck into the shoulders and arms.

2. Neurogenic Claudication

Commonly associated with spinal stenosis, this involves cramping, pain, or weakness in the legs that worsens with standing or walking but is often relieved by sitting or leaning forward (the “shopping cart sign”).

3. Loss of Fine Motor Skills

Degeneration in the cervical spine (neck) can lead to myelopathy (compression of the spinal cord). Signs include difficulty buttoning a shirt, changes in handwriting, or frequent tripping.

4. Red Flag Symptoms

You should consult a neurosurgical specialist immediately if you experience:

- Sudden loss of bowel or bladder control (Cauda Equina Syndrome).

- Profound weakness in the “foot drop” (inability to lift the front of the foot).

- Numbness in the “saddle area” (inner thighs and groin).

The Diagnostic Process

Modern neurosurgery relies on precision diagnostics to create a tailored treatment plan.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): The gold standard for viewing soft tissues, such as discs, nerves, and the spinal cord.

- CT Scan (Computed Tomography): Best for visualizing the bony architecture of the spine and identifying bone spurs or fractures.

- EMG/Nerve Conduction Studies: Used to measure the electrical activity of muscles and nerves to determine exactly which nerve root is being compressed.

- Weight-Bearing X-rays: Helpful for seeing how the spine aligns while the patient is standing, which can reveal instability (spondylolisthesis).

Neurosurgical Care: Modern Treatment Options

Most degenerative spine conditions are initially treated conservatively with physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, and epidural steroid injections. However, when these fail to provide relief or when neurological function is at risk, neurosurgical intervention becomes necessary.

1. Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery (MISS)

Today’s neurosurgeons prioritize Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery. By using specialized instruments and tubular retractors, surgeons can access the spine through tiny incisions, avoiding the need to cut through major muscle groups.

- Benefits: Less blood loss, lower infection rates, and significantly faster recovery.

2. Microdiscectomy

This is a common procedure for herniated discs. The surgeon uses a high-powered microscope to remove the small portion of the disc that is pressing on a nerve, providing almost immediate relief from radiating leg or arm pain.

3. Laminectomy (Decompression Surgery)

For patients with spinal stenosis, a laminectomy involves removing the “lamina” (the back part of the vertebra) to create more space for the spinal cord and nerves.

4. Spinal Fusion

When degeneration has caused the spine to become unstable, spinal fusion may be required. This procedure joins two or more vertebrae together using bone grafts and hardware (screws and rods) to eliminate painful motion at the segment.

5. Artificial Disc Replacement (ADR)

An alternative to fusion, ADR involves replacing a worn-out disc with a prosthetic device. This is increasingly popular in the cervical spine because it maintains the natural range of motion and reduces the stress on the surrounding “neighboring” discs.

Recovery and Long-Term Spinal Health

The goal of modern neurosurgery is not just to fix a problem, but to return the patient to an active lifestyle. Post-operative care typically involves:

- Early Mobilization: Getting patients walking within hours of surgery to prevent blood clots.

- Physical Therapy: Strengthening the “core” muscles that support the spine.

- Ergonomic Adjustments: Modifying work environments to prevent future strain.