Burst Fracture vs. Compression Fracture: What’s the Difference?

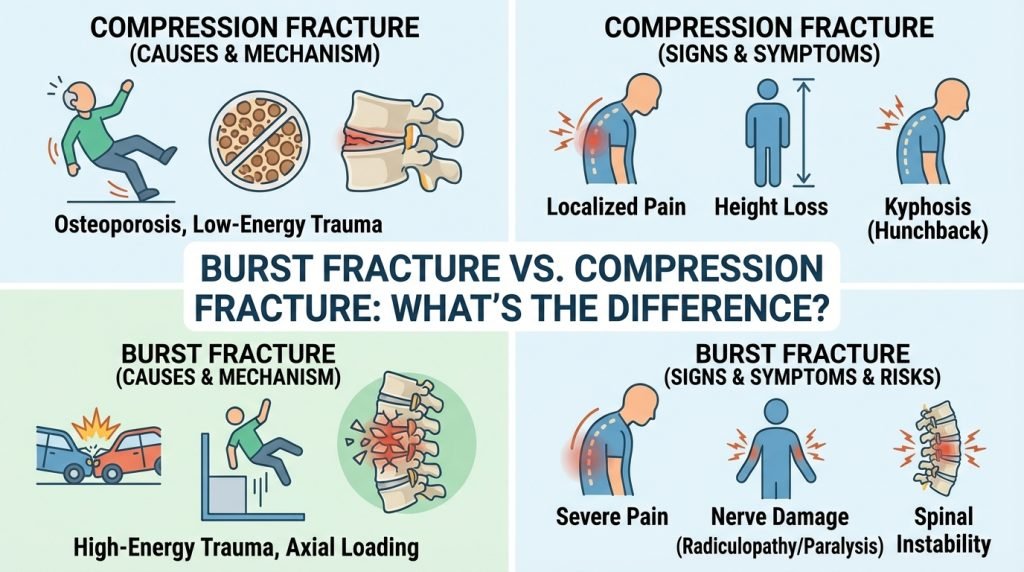

Back pain following an injury or a fall can range from a simple muscle strain to a life-altering spinal fracture. Among the various types of spinal injuries, compression fractures and burst fractures are two of the most commonly diagnosed.

While they may sound similar—and both involve the “crushing” of a vertebra—the medical implications, risks of paralysis, and treatment paths for each are vastly different. Understanding the nuances between a burst fracture and a compression fracture is essential for determining the urgency of care and the likelihood of surgical intervention.

The Fundamentals: Anatomy of a Vertebral Fracture

To understand the difference between these two fractures, we must look at the vertebral body, the thick, disc-shaped front part of the vertebrae that bears the majority of your weight.

- A Compression Fracture typically affects only the front (anterior) part of the vertebral body.

- A Burst Fracture involves the entire vertebral body, including the front and the back (posterior) walls.

In medical terms, surgeons often refer to the “Three-Column Concept” of spinal stability. A compression fracture usually involves only one column (the front), making it “stable.” A burst fracture involves at least two columns (front and middle), often making it “unstable.”

What is a Compression Fracture?

A Vertebral Compression Fracture (VCF) occurs when the front part of the vertebra collapses, but the back part remains intact. This creates a “wedge” shape.

Causes and Risk Factors

The most common cause of compression fractures is osteoporosis. When bones become porous and brittle, even minor stresses—like sneezing, reaching for a grocery bag, or a small trip—can cause the vertebra to buckle.

- Osteoporosis: Responsible for the vast majority of VCFs in elderly patients.

- Minor Trauma: A fall from a standing height.

- Malignancy: Tumors that weaken the bone structure.

Symptoms of a Compression Fracture

- Gradual or sudden onset of back pain.

- Kyphosis: A visible “hump” in the back (often called a dowager’s hump).

- Loss of height over time.

- Pain that worsens with standing or walking but improves when lying down.

What is a Burst Fracture?

A Burst Fracture is a much more severe injury. It occurs when the vertebral body is crushed by a massive vertical force, causing it to “burst” in multiple directions.

The defining characteristic of a burst fracture is that bone fragments can be pushed backward into the spinal canal. This is known as retropulsion, and it poses a direct threat to the spinal cord and nerves.

Causes and Risk Factors

Burst fractures are almost always the result of high-energy trauma. The force is usually “axial loading”—a vertical impact that travels straight down the spine.

- Falls from significant heights: Landing on the feet or buttocks.

- Motor vehicle accidents (MVAs): High-impact collisions.

- Sports injuries: High-velocity impacts in football or diving.

Symptoms of a Burst Fracture

- Intense, debilitating back pain.

- Neurological Deficits: Numbness, tingling, or weakness in the legs.

- Inability to walk.

- In severe cases, loss of bowel or bladder control (a medical emergency).

The Danger of “Retropulsion”

The most significant medical difference lies in the posterior wall of the vertebra.

In a compression fracture, the posterior wall acts as a shield, protecting the spinal cord. In a burst fracture, that shield is shattered. When bone fragments are “retropulsed” into the spinal canal, they can compress the spinal cord or the cauda equina (the bundle of nerve roots at the end of the spinal cord).

This makes burst fractures a potential neurosurgical emergency. If a patient experiences weakness or loss of sensation following a spinal injury, doctors must immediately check for a burst fracture using advanced imaging.

Diagnostic Imaging: How Doctors Tell the Difference

Because these fractures can sometimes feel similar initially, imaging is the only way to confirm a diagnosis.

- X-Ray: Often the first step. It can show the “wedge” shape of a compression fracture or the loss of height in a burst fracture.

- CT Scan: This is the most important tool for burst fractures. It provides a cross-sectional view that shows if bone fragments have entered the spinal canal.

- MRI: Used to evaluate damage to the spinal cord, ligaments, and discs. It helps determine if the injury is “fresh” (acute) or old.

Treatment Options

The treatment plan depends entirely on whether the spine is “stable” or “unstable.”

Treating Compression Fractures

Most compression fractures are treated conservatively.

- Pain Management: NSAIDs or nerve blocks.

- Bracing: A back brace (TLSO) to limit movement and allow the bone to heal.

- Kyphoplasty/Vertebroplasty: A minimally invasive procedure where medical-grade bone cement is injected into the vertebra to stabilize it and restore height.

Treating Burst Fractures

Burst fractures require a more aggressive approach due to the risk of neurological damage.

- Non-Surgical: If the fracture is stable and there is no neurological damage, a specialized body cast or rigid brace may be used for 10–12 weeks.

- Surgical Stabilization: If the spine is unstable or fragments are pressing on the nerves, surgery is required.

- Decompression: Removing bone fragments from the spinal canal.

- Spinal Fusion: Using metal rods and screws to lock the vertebrae together, preventing further movement and protecting the spinal cord.

Long-Term Outlook and Recovery

Recovery from Compression Fractures

For most patients with osteoporosis-related compression fractures, pain significantly subsides within 6 to 8 weeks. The primary goal is preventing future fractures through bone density treatments (calcium, Vitamin D, and bisphosphonates).

Recovery from Burst Fractures

Recovery from a burst fracture is more complex. If surgery was performed, the patient may require physical therapy to regain strength and mobility. The recovery timeline can range from 3 to 6 months. If neurological damage occurred at the time of the injury, long-term outcomes depend on the severity of the spinal cord compression.